Exploring Collective Identity Through Medium Format Film Photography with Vân-Nhi Nguyễn

11 Share TweetGrowing up in Vietnam, photographer Vân-Nhi admits she has a hard time connecting with a sense of national identity, as a young person living in the 21st century. With the country still feeling the effects of a war that happened half a century ago, and with the rapid development of its economy, it's an interesting yet confusing time for this South East Asian country. Nhi creates her own world of photography, blending archival family albums depicting the past lives of her relatives, with her own images of 21st-century Vietnamese youth, mixed with Western references, local stereotypes and even culturally impactful memes.

Greetings Vân-Nhi! Can you introduce yourself and tell us how you started your analogue journey?

Hi, my name is Nhi, and I'm currently based in Hanoi, Vietnam. My practice is just mainly about recalling my memories in response to my current struggles in hardships, love, life, and everything else. In my practice, I like to use motifs, like floral motifs, and common stereotypes that I use repeatedly as my way of building up images because I want to question where these kinds of motifs and stereotypes stem from.

You started out as a graphic designer and then switched to photography. How did that come about?

So, my background is actually from drawing and painting and then I gradually just moved to photography. And then graphic design came in a little bit late because I kind of needed to make a living. I do photography full-time now and I'm trying to make the switch to more photographic art, trying to expand this idea that photography can be more than just the image.

How was your experience of art school? Is there anything from that period that still resonates with you?

I studied in Canada and what really struck me was how Western the whole course was. The entire degree focused on the narrative of the Western world and when they tried to branch out into Asian or African art they would lump it together as oriental art. It felt exoticized. I had a lot of problems with using the word "oriental". They try to be international, yet the narrative is so monolithic and just extremely questionable. So after I finished school I began really question myself, do I want to carry on with that way of thinking, or do I want to unlearn all this?

This is what led me to decide to actually use these stereotypes and motifs that Western art used all the time and reappropriate this into my photography, to question this narrative. Why do I only know about Western art? And why is Western art the only thing that is being taught to Vietnamese kids? Building a dialogue between me, being a person living in this Vietnamese society, yet not knowing who I am, or what kind of community I belong to. And then use all these motifs within the Western world to question all of these other things within myself.

Did studying abroad make you appreciate your upbringing more?

It's so Vietnamese of me to take everything around me for granted as a child. I have always thought that if I want to study art, then what's around me is probably not enough and I have to go abroad. It took that step for me to be outside the country and to recognize what I am lacking and what I have at the same time. Afterward, I came back to Vietnam to focus on trying to find a way for me to say what I wanted to say which heavily focused on my own upbringing.

The more I looked into it I realized that my story is not unique and there are millions of kids like that in Vietnam, who kind of struggle with who they are and where they fit in. It sounds so angsty and so teenager, but I feel like, at the same time, it is something that is not seen within photography or art in general because for some reason there is hardly any representation of Vietnamese youth worldwide. So, doing all this work has me reconnecting with myself, expanding my community, and whatnot. It's more about the process than the actual outcome, but I'm kind of glad that the flow of the photograph itself can convey what I want to say.

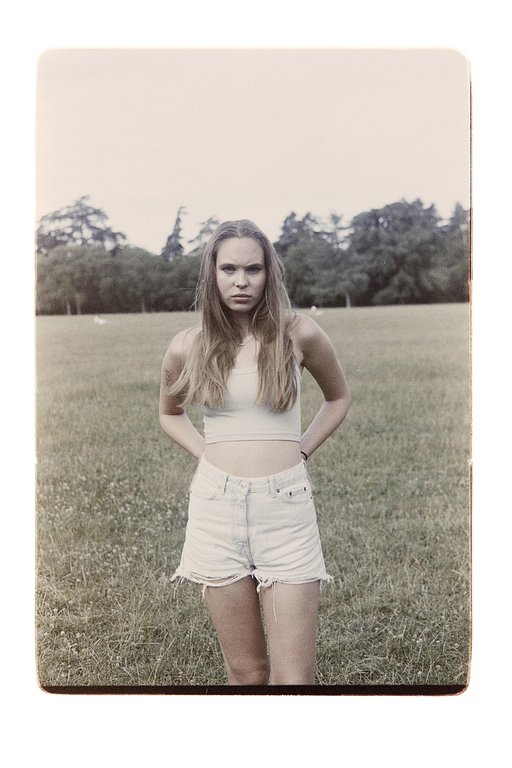

Talking about your series As You Grow Older, what kind of tools did you use to capture the photos and essence of what you wanted?

I shot this all on film and I used my Mamiya RB. There were a few times that I tried to use a large format but that flopped. Since it's so large it's hard to find a focus point with that large format camera. I couldn't get the results I wanted. I had quite a long time just thinking about this. I feel it's all part of making the work. Every aspect of it should be taken into consideration, even the smallest detail. Like why do I have to use a studio-like setup? Or why do I have to use a set? Instead of just capturing whatever candid image there is? Or why do I have to use a medium-format camera? And it's all taken into consideration.

Since you're talking about reclaiming the past, have you ever thought about using the cameras that were used in the Vietnam War? I know the Nikon cameras were used throughout the war.

It never really crossed my mind to use a camera from the war, but I think that by already using a medium format film camera I actually feel I already have a dialogue with the past.

For your series As You Grow Older, could you break down one photo and tell us more about the ideas behind it?

There is one image where there are two guys in a very dark background and they're posing in a way that mimics Michelangelo's Pieta. I think that image represents my process throughout the entire series because my whole thing is about motifs and stereotypes. It’s referencing Western art, and it clearly doesn't even mean anything biblical but looking at it from my perspective this scene talks about the comedy of everyday life. For people here, it looks as if a father gave birth to a son rather than the Pieta.

The process for these images is very collaborative since the initial idea actually was supposed to reference another painting but it just was not working out. So I showed my subjects the reference painting and asked what they thought about it. I always try to ask my subjects to look at the image that I give them, so they can also interpret it differently or however they want. To me, the subject should have a little bit more power than the photographer because as we know photography is such a violent sport. The fact that the Pieta idea didn't come from me but rather from my two close friends who were subjects made it feel like such a full-circle moment. I finally get the subject to understand what my work is, how I want the people in my work to respond to me, and how I want to respond to the people in my work. I think this was really early in the series. So this became the stepping stone and helped me carry on the work and how to continue that work with my other friends.

So basically you reference something Western but then give the power to your friends on how they want to interpret it, and make sure that they're the ones calling your shots. That's very interesting because I agree with you that photography is violent. There's a clear power dynamic, for sure.

I agree with you. The way I was taught photography in school was really violent in the sense that it's all about control, power, and selectively choosing what is important to capture. I don't think that there is something less important and I feel everything deserves to be talked about. For me, being able to talk to my friends and having them understand why I do what I do and establishing this relationship before making the image is quite an important step in the process. Because after you get it out of the way then the image kind of flows very naturally. They can give you feedback and then you can also give them feedback and it's a mutual exchange.

How would you describe a young Vietnamese person nowadays?

I can only somewhat say that for my group of friends as they are the main characters and protagonists of the series, but that's all I can vouch for. Vietnam now is completely different from what it was probably just two years ago, the economy just booming. So that's why, you know, everyone's been changing so fast. And to me, I feel like every time I look back at this group of friends, they are always constantly in some sort of crisis. That sounds so bad, but I feel this sense of trying our best to carve out a space for ourselves within this, ever-changing, landscape of Vietnam.

It's just a constant fight, because most of them are queer. And you would think that after all this time, there's an acceptance within the queer community but then there are still these little wars between the groups of people that kind of punch down all the progress that you've made so far. Though there's this sense of individualism within people, within my community and friend group, there's little to none of that here. So it's always nice to have that support from them and other people.

For you, how has the medium of photography tried to patch or fix the problems of post-colonialism?

What I enjoy about photography is that there's the idea that it has to be real. This discourse is so old it is something people still believe in. However, for me to shoot these “fictional” still documentary images that also speak about the past and the future, these images that I take bridge together a larger community of these found images of my parents and grandparents, and all these images are somehow in dialogue with one another. Whether it's from my parents or something new that I took. These images collectively become a photo album of these two things merging to become a larger story being told of the past and the future.

In Vietnam we don't have a photographic archive at all. There’s no official archive so we don’t have a base to believe in what happened during the war or in the past. What we have are the images we took ourselves through cameras that every family has. I used the idea of a family archive which is also a historical archive that we can use as a starting and ending point to bridge together different generations. It’s really like seeing is believing. You can see my family and what my friends are like as they emerge together and become a giant world. The past can be like this and the future is reflected in it as well. As you look through the entire series it unfolds unto itself. I try my best to make the work as easy to understand as possible since I’m not too good at explaining.

You mentioned that your work also challenges stereotypes and subverts common misconceptions about Vietnam. Can you share some examples of these stereotypes?.

So I come from a village, quite far from Hanoi and when I started shooting the series I started to look inward and started to shoot landscapes and domestic scenes that felt closest to me. But as I brought it out to multiple editors, they pointed out that there's this stereotype of the Vietnamese only being "village people" especially in Northern Vietnam. I do recognize that it is notable, but because this is where I'm from, at that time I didn't pay much attention to it. However, the stereotype is that people like to look at Vietnam as a country that cannot be saved from the war and that the war is the only thing that should be talked about when you talk about Vietnam.

And so for me, I just wanted to talk about the youth and how we want to be perceived, and how much fun we're having and how we're loving. In a way it challenges these notions of being perceived as a war-torn country, even though Vietnam is moving at such a fast pace.

Your style caught the eye of photographer Peter Do and he invited you to be part of his curation of A Magazine. I know you have mentioned how you are done with fashion so what made shooting for him different?

I always say that I'm really done with fashion photography, but when Peter Do reached out to me to shoot for A Mag I was really excited because Peter is one of those few Vietnamese people that I look up to, solely for how he carries himself and how a boy from Biên Hòa can work so hard to build himself this empire. I really do appreciate his effort and his work. Despite knowing Vietnamese, he always feels out of place because whenever he goes back to Vietnam people don't speak to him in Vietnamese anymore, they only speak to him in English. I understand that because for one or two years people also did the same to me which I felt really sad that you don't think that I'm Vietnamese despite me being born here.

For me being able to help him realize this series of images where we shot all these minimalist and very structured clothes which are very him, alongside extremely South Vietnamese elements conveyed a sense of trying to belong into a place where you know you no longer identify with. He doesn't want to be Vietnamese or he doesn't want to be American, he just wants to be himself and it's quite nice to be able to shoot that, and help Peter realize his own feelings into images. This shoot was probably the most stressful job I've ever done.

You recently showed a new body of work called Mother Dearest. What's the difference between that work and your previous work As You Grow Older, despite it tackling similar themes?

What I generally do with all my work is that I always want to talk about my own experiences through collective memories and reconstructing memory into an image. But for Mother Dearest, I want to talk specifically about Vietnamese new love, which people and even I myself don't see as much. So even for me, it's something new and as I dive deeper into the subject I also try to incorporate meme culture because it really reflects the uniqueness of the Vietnamese. You do not get to see that as often as compared to Western memes.

I guess an example here is that the way that we show love here is different. So one pastime to show love here is just doing wheelies. People go on bikes, and they do wheelies. They pick up the head on the bike and drive with the wheel in the air. It's extremely romantic in the Vietnamese context because in Vietnam when a guy does a wheelie with a girl in the back, you know that they're in love. So for me to be able to convey all those pastime activities into images, I feel it is worth being seen and worth being talked about because you don't get to see this online, and even I don't get to see that so often online.

For the show, we turned the whole gallery into a studio house, which is the most common domestic space in Vietnam. It has a bed and living room all in one space. When you move around the gallery it has drapes and fabrics all covered in floral motifs that I use quite often in my past work as well. There was this one review from a critic who wrote that the show sees love as this revolution that was going to change the landscape of Vietnam, which I feel like it's so funny. But at the same time, it's very precious that they see the entire show blur the ego of the different artists to talk more about love and how the youth is moving as a whole. The show really made use of collective memory. Everything even down to the smallest detail the fabrics, the flowers, and the stickers that are used throughout the entire thing were drawn from memories, places of our deepest darkest secrets, and a lot of things that you get to see as a Vietnamese person as you were a young child, but then it gradually started to disappear as the country moved into this more capitalist way of working and living. Right now everything is clean, everything is sterile so that it can sell better. The whole motif of the exhibit created this maximalist feel of what love is in our day.

You were accepted into the 18th edition of Angkor Photo. Could you share your experience and some of the things you learned while attending?

During Angkor, I personally did not make the work that I actually enjoyed since the workshop is just seven days, and you create a body of work from start to finish in that amount of time. So to me, it does not reflect fully who I am, because there's no meditating on the series at all. But during that process, I made a lot of really great friends who I remain in contact with, especially from the South and Southeast Asia region. And, you know, it's such a great group, especially for last year, because we actually get to do a lot of things together. Angkor did teach me how to work harder, extremely hard.

It's such an insane experience that I feel all photographers should have at least once in their life if they want to completely change how they work. Before, Angkor, it would take me months to produce an image because I kept thinking about how I could carry out an image, the best way that I could. But as Angkor happened, I became more proactive in the way that I work and the way that I think, and that I actually do have to involve other people into my process if I want to speed things up, and if I want to make it better. It's a process of learning how to adapt in such a short period of time.

When you usually shoot, what gear do you gravitate towards?

I did mention before the Mamiya RB 6x7 and most of the time, just one light because I strive to go down as minimal as possible so that the subject is what matters the most and not like the other noise in the background. I like to switch between one or two strobe lights and I mostly use slide film like Velvia 50 and if I can't get my hands on that I use Kodak Ektar.

Why do you still choose to use film?

Film is very important to me, especially for the work I'm doing because it brings this sort of dialogue with the past and the future that I'm talking about within all of my work. The constant use of film is like a medium that bridges these memories from before and the new memories that I'm trying to convey through my work.

Have you ever used Lomography products when shooting film?

I used a lot of Lomography films for my personal images before I switched to slide film for this project. For its quality and accessible price point using Lomography film is really a great deal, especially CN400 . I use it quite often because you can just shoot it everywhere and you'll get good colors. I use it to shoot more random things like pictures of my mom for her new Facebook profile, which is the most important picture ever.

Where do you see yourself and Vietnam in the next five years?

I want to create for myself a community of younger photographers who are interested in a fine art interpretation of photography. I'm trying to create this environment where everyone feels welcome to come in and talk about photography and how they want to develop something. In Vietnam, I don't think there's a space for fostering younger photographers who want to use photography outside of the phone. I want to build it slow with a solid foundation which takes a lot of time, but it is something I want to achieve in five years.

We thank Nhi for her photos and words. You can keep up with her by following her Instagram.

written by rocket_fries0036 on 2024-04-29 #culture #people #places #art #people #slide-film #memory #documentary #youth-culture #vietnam #apac #interview-van-nhi-nguyen

No Comments